The distinguished Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka has just published his first novel in almost a half century, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth – a scorching satire on contemporary Nigerian society that teems with life, rather like one of the big books by Charles Dickens (Bleak House) or William Thackeray (Vanity Fair) – or even, if you want a more classic reference point, the effervescent social satire of Gargantua and Pantagruel by the Renaissance writer François Rabelais. Soyinka’s use of the word “happy” is heavily ironic; his Nigeria is dominated by corruption, sleaze, self-interest, and brutality upon brutality. “Happiness” is just a government PR slogan used to cover up numerous ugly realities. (One is reminded of the empty happiness in another satire, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.) Soyinka even invents some new ugly realities to make a point: in a dystopian kleptocracy like his Nigeria, what could possibly beggar the imagination?

Satire has been around for a very long time. In one of its oldest recorded forms, painted papyri from ancient Egypt, the natural order of things is amusingly turned on its head. A 3,000-year-old papyrus in the British Museum shows a lion playing a board game with a gazelle (later in the sequence the two animals are having sex) and a cat herding geese. This is satire at its most gentle, very obliquely poking fun at the status quo, but if we view it as a cartoon it seems a direct ancestor of the cartoon satire of our day, such as Doonesbury by Garry Trudeau or the many sight gags in the animated TV series The Simpsons.

Political satire often sets out to do as much damage as possible, to sweep away; this perhaps accounts for its savagery

John Mullan, Professor of English at University College London is a literary polymath, but his most recent book, The Artful Dickens, portrays Dickens as an ingenious satirist and “innovator who broke all the rules”.) When asked if satire should set out to change the world, Mullan tells BBC Culture, “Satire is a negative art… it does not come with some kind of manifesto for a better world. It tells you what’s wrong; it doesn’t tell you what you should do.” So political satire often sets out to do as much damage as possible, to sweep away; this perhaps accounts for its savagery.

Satire as it is commonly understood in the West – as art that mounts a darkly humorous socio-political critique – really coalesced in ancient Greece and Rome, known to us through the works of, for instance, the Greek writer Aristophanes (5th to 4th Centuries BC) and the Roman writers Horace (1st Century BC) and Juvenal (1st and 2nd Centuries AD). Juvenal excoriated the hypocrisy, lack of compassion, pomposity, and avarice of contemporary Roman society in his poetry, and it is to him we owe such quotations as “Who will watch the watchers?” and “Honesty is admired, and starves”. The Anglo-Irish writer and satirist Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) famously struck an explicitly Juvenalian pose in his Modest Proposal by suggesting that the aristocracy put the surfeit of poor children to good use by eating them. One could argue that Juvenal’s lacerating spirit is still present in much satire today.

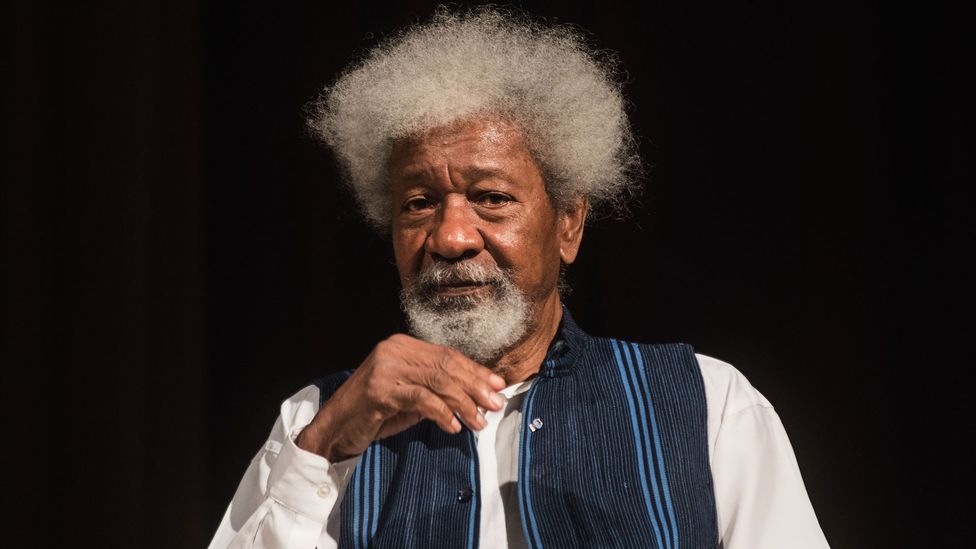

Despite penning plays, poems and essays, Wole Soyinka hasn’t written a novel since 1972 (Credit: Getty Images)

Who will watch the watchers, indeed? There are direct echoes of Swift’s cannibalism in Soyinka’s Chronicles, where one of the central characters, a surgeon called Dr Menka, who spends his days dealing with mangled victims of the Jos region’s endemic violence, discovers a thriving underground market in human body parts for ritualistic purposes. Soyinka deplores the state of contemporary Nigerian society; he has spoken of “cannibalism, of a strange kind, … a society which is actually eating itself, sort of self-directed cannibalism and the deterioration of our humanity”.

In Chronicles, Soyinka cites a Yoruba proverb: “When we encounter an elephant, let us admit that we have seen the lord of the forest, not offhandedly remark that we have seen something flash across our sight.” He has dedicated his career to addressing the elephant in the room – as well as the circus around it. (Juvenal said that people long for just two things, “panem et circenses”, or bread and circuses.) The trick is to avoid the elephant sitting on you.

Dangerous fiction

Satire has a way of putting its practitioners on the cutting edge of politics, and often that is a risky, not to say life-threatening, proposition. As Mullan points out, even the most fearsome, seemingly invulnerable leader usually can’t stand being laughed at. (Mullan cites Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, both of whom have been accused of humourlessness.) It is one thing to, for example, remorselessly send up the British prime minister and cabinet using puppets, as the successful TV series Spitting Image did (it represented Margaret Thatcher as a demonic tyrant and even a pal of Adolf Hitler); such satirical targets traditionally have very little comeback in healthy democracies except to complain. President Reagan, repeatedly mauled by Spitting Image, is reported to have phoned NBC and asked them to cancel broadcast of the show, to no avail.

It is quite another thing to devote a lifetime to needling Nigerian regimes and other elite cliques, as Soyinka has done: during the Nigerian civil war he spent 22 months in prison, and in 1994 he fled the country after enraging Sani Abacha, a military dictator who pronounced a death sentence on him in absentia. But Soyinka has always lived on the political brink. His 1986 Nobel Prize, his sheer stature, may or may not have afforded him some protection. Others have not been lucky: Chronicles is dedicated to two Nigerian political activists, the journalist Dele Giwa and lawyer and politician Bola Ige, “both cut down by assassins”.

According to Penguin, Vladimir Sorokin’s ‘Day of the Oprichnik imagines a near future too disturbing to contemplate and too close to reality to ignore’ (Credit: Getty Images)

Despite its hazards, the kind of novelistic satire that incenses political autocrats is alive and well. In addition to Soyinka, two other examples of this in the world today are the work of the Russian writer Vladimir Sorokin and of the Chinese writer Yan Lianke.

Sorokin (born 1955) has had a high profile in Russia for many years, but his works have only gradually found a following in English translation – two of his books, The Blizzard and Day of the Oprichnik, were enshrined in the Penguin Modern Classics series in 2018. The critic Michael LaPointe calls Sorokin’s output “one of the most transfixing bodies of work in world literature”. Day of the Oprichnik (2006) is set in 2028 in a dystopian Russia, which is extremely violent and strongly redolent of Anthony Burgess’s book A Clockwork Orange (1962). Like Clockwork, the former’s nasty ironies are not subtle: Russia is now ruled by a tsar again, and the book follows one of his henchmen, a strapping specimen of Russian masculinity, as he murders, rapes, and tortures his way through a day. This thug at one point daydreams about the “state cauldrons boiling” and rendering human fat, which drips into the snow and “swirls like frozen mother of pearl… Splendid. Delightful.” Day of the Oprichnik is generally regarded as a “savage little fairytale about Putin’s Russia”, and it duly got him into some sinister political hot water for daring to be an enemy of the state.

A scene from a theatrical production of Vladimir Sorokin’s novel The Norm performed in Moscow in 2019 (Credit: Sergei Fadeichev\TASS via Getty Images)

Sorokin’s writing is hallucinatory, laced with grim humour, but never really funny ha-ha. Mullan makes the point, and so does Jonathan Coe in a brilliant article about political satire in the London Review of Books, that actual laughter and satire might even be seen as opposed: one forces us to look at an ugly situation by amplifying it, while the other defuses the situation by trivialising it and potentially putting us at our ease. (Coe’s article is actually about Boris Johnson’s capacity to play the fool, to “laugh at himself”, which Coe views as a sly strategy to evade criticism. The article was published long before Johnson became prime minister, and his brand of tomfoolery became emblematic of an era.) Since mere laughter at a situation may be co-opted, the smile may need to be wiped off people’s faces before it can fully form.

People live like dogs in this society. I dream of being able to bark out loud in my books, and of turning my barking into exquisite music – Yan Lianke

There is plenty of infernal, sardonic irony in the Chinese writer Yan Lianke’s books, which send up life in communist China. Yan (born 1958), who continues to live in China, is often tipped for a Nobel Prize; he has made a long career out of trying to avoid censorship by finding oblique ways to criticise Chinese politics and society, though he seldom succeeds. Currently most of his work is subject to an official ban. His style is experimental and absurdist; he has said, “The reality of China is so outrageous that it defies belief and renders realism inert.” Yan’s novel Serve the People! (2005) features a couple who have outrageous sex while defiling the memory of Mao Zedong in various ways. Dream of Ding Village (2006) satirises the “plasma economy” (the government-managed trade in blood) in Henan province in the early 1990s, which resulted in hundreds of thousands of people contracting HIV. In a moving dispatch to the New York Times in 2012, Yan wrote: “People live like dogs in this society. I dream of being able to bark out loud in my books, and of turning my barking into exquisite music.”

Some of Yan Lianke’s works have been banned in China, and he has said that he self-censors while writing to avoid state censorship (Credit: Roberto Ricciuti/Getty Images)

In the age-old wrestling match between satirists and (political) vice, who wins? Mullan suggests that satire is a way of laughing at something we’re powerless to change – which would seem to be saying that satire has no social traction. When asked if he had hope for Nigeria’s future, Soyinka replied, “Oh, hope. Again that’s another word that I don’t use.” Soyinka (like Sorokin and Yan) is reluctant to use the word hope. All these writers are taking on much bigger opponents – and yet they continue to write.